THIS SUMMER, ALL AROUND THE WORLD people celebrated the 50th anniversary of one of humankind’s greatest technological achievements: the successful Apollo 11 mission to the moon. Riding in the wake of Neil Armstrong’s famous small step came a steadily rising tide of technological innovation that has carried us well into the 21st-century.

Interestingly, however, the Apollo mission that perhaps produced the most consequential image for the world to see was in fact lucky number 8, which in the previous year returned a view none had ever seen before: the Earth itself. The image of our planet suspended in space, aptly named Earthrise, was taken by American astronaut William Anders while he and his three-man crew travelled the moon’s orbit. The stunning visual proved to be the key in turning humanity’s gaze away from the stars and back to our celestial body at hand. Earth’s place as a lonely kingdom of water and life in the solar system shook centuries of misguided observations and damning dogma. The message became clear. The Earth, too, deserves our gaze and wonder.

The new perspective Earthrise conveyed brought momentum to a budding environmental movement. Recognizing the rarity of our situation encouraged followers to find ways to deepen our connection to the natural world, an idea that reached the design and architecture community with Edward O. Wilson’s biophilia hypothesis and subsequent biophilic design. I had originally planned to write about the evolving benefits of biophilia and nature-centric design, but the challenges of a changing climate and subsequent survival scenarios seemed to call for more.

In 2018, NASA held a competition to design and prototype a living space for astronauts to inhabit on Mars. The criteria for such a build was extensive and required each team to study all facets of construction on the red planet, including the transportation of materials and tools that would be used to complete the build.

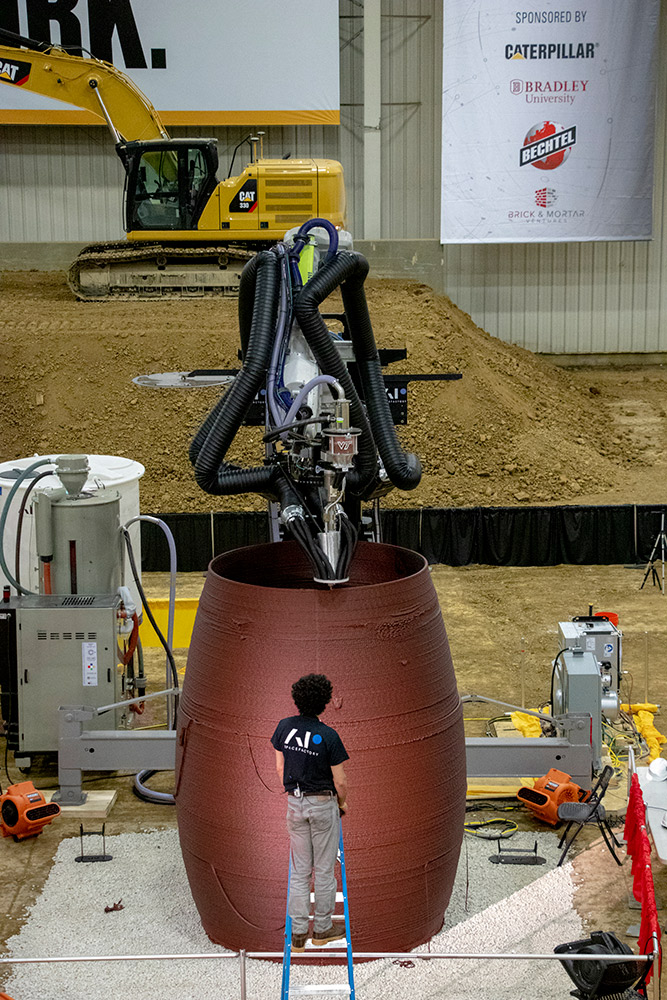

If you’ve ever taken a look at space architecture, it’s no surprise to learn that the primary method of fabrication employed is large scale 3D printing. Utilizing cutting edge robotic technology, it is now possible to construct viable building structures using large extruders that can output a variety of materials from concrete to various biocomposites. From Austin to Dubai, these additive manufacturing adventures have been popping up in recent years. And the winners of the NASA challenge are seeking to take the lessons learned from designing for space and bring them back to Earth.

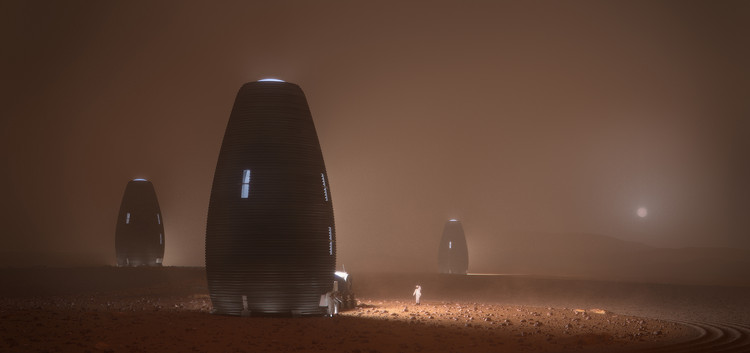

Due to the strict demands of interplanetary construction, the key features of AI SpaceFactory’s award-winning MARSHA (Mars Habitat) design are deeply rooted in sustainability and resilience. The dual pod-like structure is cylindrical, creating a separation between the outer shell and the inner habitat structure, which allows the two parts to be constructed (as well as serviced) separately. The outer shell is also designed to subtly flex according to likely dramatic shifts in weather and climate and features a skylight roof that provides natural lighting throughout the entire inner structure. Meanwhile, the inner shell can be designed freely to cater to the physical and emotional needs of humans living on another planet – without having to simultaneously address structural concerns.

Moreover, the proprietary biopolymer (a PLA reinforced by basalt fiber) makes MARSHA optimized to handle intense internal and external thermal and pressure conditions on Mars. According to Head of Space Architecture Jeffery Montes, the solution was tested and proved to “outperform concrete in all relevant metrics including superior tensile and compressive strength, superior durability under extreme temperatures and higher ductility.” The material also showed promise of superior radiation absorption, thermal resistance and is both recyclable and biodegradable.

TERA brings MARSHA down to earth

The AI SpaceFactory team recently followed up their NASA challenge success by launching a crowd-funding campaign to realize their MARSHA vision here on Earth in the form of TERA. TERA is being built from the same 3D printing technologies and compostable materials AI SpaceFactory designed for longterm, sustainable life on Mars with the MARSHA project. Seeking to shed light on the massive environmental and operational costs of construction worldwide, TERA reimagines how we design and build on our planet by combining widely available materials with wildly powerful technologies.

Staying true to their recyclability claims, they plan to reuse the biopolymer from their prototype and build a fully inhabitable, two-story structure off the Hudson River just a couple hours north of New York City next spring. They estimate the core structure can be 3D printed in a few weeks and supporters of the campaign can look forward to spending a night in the award-winning Martian habitat, which like William Anders’ photo, is thankfully being brought back to Earth.

More next issue on TERA and how the project will be impacting future biophilic and sustainable, resilient design.

This article was originally published in Technology Designer.